As software development evolves from human programming activities to AI-assisted activities, our efforts will concentrate more on expressing intent concisely and precisely through story telling. Many of our failings in software are due to our inability to foresee everything we need, before we build. Then, the flawed design and implementation imposes crippling constraints on what can be added or fixed later. Even as we learn from our mistakes, often the sunk cost of software misleads us into thinking that a rebuild will incur that cost again. That is why some things never get fixed properly or in a timely fashion until a competitor offers a total replacement.

AI-assisted software development offers hope that the toil of grunt coding ceases to bottleneck progress. The heavy boat anchor of legacy code is not an insurmountable burden if tools can automate the rewriting of thousands of lines of code in minutes, provided a precise enough context and intent can be expressed through documents and prompts.

The question is, what should that context and intent look like? That answer has plagued software development since the beginning. Various methodologies have offered techniques that have yielded mixed results in how humans analyze requirements and design solutions. A mix of languages (metamodels) and notations (visual, textual) have been used for modeling. It has always been a struggle manifesting a god’s-eye model into software realization, because of the enormous human effort it takes to meticulously reinterpret a conceptual model into precise machine instructions.

AI-assisted tools will motivate us to race faster toward inventing more concise and precise languages and notations for expressing conceptual models, so that automation can reduce the burden of software implementation. Methodologies will further concentrate our efforts on expressing context and intent, as “just a matter of programming” (IYKYK) is reduced to large scale inferencing.

Paleo-software engineering methodologies include structured, functional, object-oriented, and test-driven. Industrial and commercial problem domains are too large and complex for any human to reason about all at once.

We often approach modeling from a 30,000 ft view, as though we are cruising at altitude in an aircraft and describing the lay of the land below. There are structural and behavioral descriptions, as well as non-functional qualities (so-called ‘-ilities’). This mental model provides a skeleton, but “the devil is in the details”. Such a conceptual model is essential for providing a vocabulary, otherwise we cannot even begin to articulate anything in our analysis and design journey. That journey involves “peeling the onion” to explore finer levels of detail, until there is enough understanding for humans to write code. Human error and the imprecision of human expression and interpretation plagues this process.

To be able to speak about a problem domain, we must first establish a vocabulary of nouns for structures and verbs for behaviors. Naturally, this vocabulary expands to include relationships among structures and between the nouns and verbs in how subjects act against objects under various circumstances (states) and with constraints.

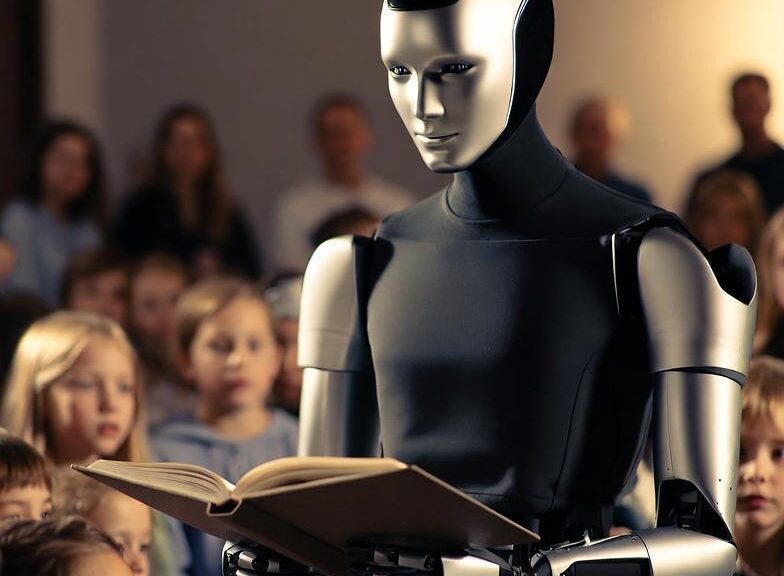

Analysis and design is about describing an imaginary world that becomes real. It is story telling. The purpose is not to entertain. It is to author a future that will be manifest in machines and the humans who use them.

There will be a gap in descriptive detail, as we begin telling the story from a 30,000 ft altitude, and we descend to bring more granular elements into focus. Traditionally, the remaining distance between story telling and machine executable code is closed by human effort. Developers fill in this gap. We aspire for this toil to be replaced by machine inferencing. Human inference produces imperfect results because of flawed (incomplete, inconsistent, ambiguous, incorrect) descriptions. Machines will give similar outcomes until we improve story telling.

We should recognize that AI-assistance in software development is not limited to coding. Story telling is in a Large Language Model’s wheelhouse. With the totality of human knowledge at its disposal, any problem domain can be largely understood by AI through its ability to research.

The creative aim of software development is to make incremental (sometimes revolutionary) improvements on the current state. Therefore, the vast majority of analysis and design is to build tooling to facilitate what we do today largely unaltered. Innovation targets a few narrow pain points that yield valuable benefits.

AI-assistance in story telling could provide the mundane description of the current state of a problem domain, leaving the narrow creative portion to human imagination. A machine researcher can do far better than a human in writing stories that provide complete coverage, that are accurate and consistent, and that provide enough detail to leave no dangerous holes.